Section 1

PFAS

The Global Chemical Challenge Threatening Health and the Environment

Section 1

PFAS: The Global Chemical Challenge Threatening Health and the Environment

What Are PFAS and Why Are They a Problem?

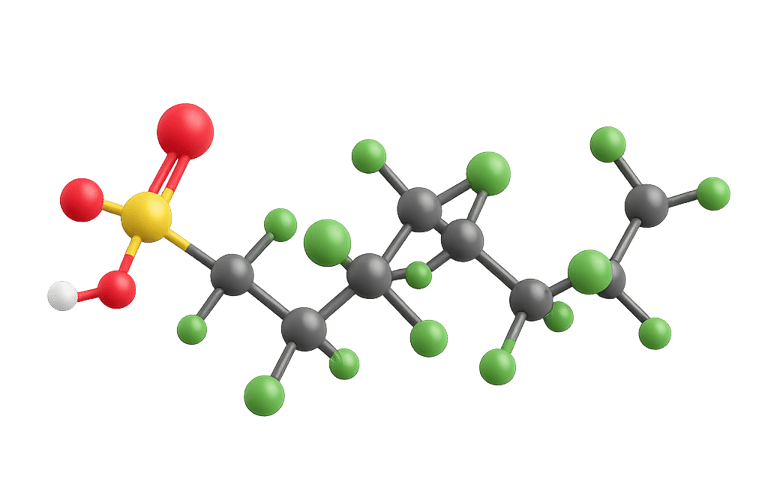

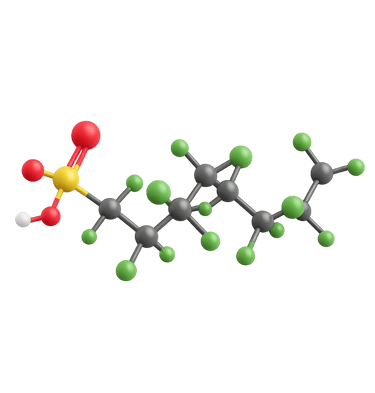

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), often referred to as “forever chemicals,” [1] are synthetic compounds prized for their water- and grease-resistant properties. Since their first synthesis in the 1930s, they’ve been used in countless everyday products—from non-stick cookware and waterproof clothing to firefighting foams and food packaging.

But the very same stability that makes PFAS useful also makes them nearly impossible to break down. Over decades, PFAS have spread across soil, air, and water systems worldwide, turning into one of the most pressing environmental issues of our time.

By the year 2000, PFAS compounds like PFOA (perfluorooctanoic acid) and PFOS (perfluorooctane sulfonic acid)had been detected globally. Their resilience means they accumulate in ecosystems and the human body, creating serious health and environmental challenges.

PFAS Contamination Across the Environment

PFAS are now found almost everywhere:

Watersheds: Strict regulations are forcing improved treatment for drinking and reuse water.

Soil: Industrial and defence sites face cleanup liabilities.

Air: PFAS spread during manufacturing and through refrigerant emissions.

Wastewater: Landfill leachate and industrial discharges contaminate treatment systems.

Concrete and Infrastructure: Airfields and refineries face embedded contamination.

Crops and Food: Irrigation and biosolid use have raised fears of PFAS entering the food chain.

The challenge is global—and the ingenuity that created PFAS is now being redirected toward eliminating them.

Understanding the Different Types of PFAS

PFAS share a defining feature: strong carbon-fluorine bonds, among the most stable in chemistry. The OECD defines PFAS as fluorinated substances containing at least one fully fluorinated methyl or methylene group.

There are two main categories of PFAS:

Polymers – often used in industrial coatings.

Non-polymers – the focus of environmental regulations due to their persistence and toxicity.

Non-polymers are further divided into:

Perfluoroalkyl substances, where all hydrogen atoms are replaced by fluorine.

Polyfluoroalkyl substances, where only some carbons are fully fluorinated.

Among these are PFAAs (perfluoroalkyl acids), which include:

PFCAs (perfluoroalkyl carboxylic acids)

PFSAs (perfluoroalkyl sulfonic acids)

Long-chain PFAS (such as PFOS and PFOA) are more persistent and bioaccumulative, while short-chain PFAS are being increasingly detected due to shifts in manufacturing.

Researchers estimate there are over 27,000 types of PFAS, though experts argue that regulation should focus on the roughly 256 most commonly used variants.

Health Risks Linked to PFAS Exposure [2]

Scientific research continues to uncover how PFAS affects the human body. Studies have connected PFAS exposure to:

Increased cholesterol levels

Liver and kidney toxicity

Thyroid disruption

Immune system suppression

Reproductive and developmental harm

Certain cancers

Human exposure typically involves multiple PFAS compounds, making it difficult to isolate exact dose-response relationships. Still, the most consistent findings for PFOS and PFOA include elevated cholesterol, higher uric acid, decreased birthweight, increased liver enzyme levels, and reduced vaccine response.

While more research is needed, the bioaccumulative nature of PFAS means they can remain in the body for years, compounding long-term risk.

How the World Is Regulating PFAS

PFAS regulation is evolving rapidly around the globe, focusing on three major areas:

Product control

Drinking water limits

Environmental cleanup standards

In 2000, 3M announced it would phase out PFOS production. By 2022, the company pledged to stop all PFAS manufacturing by 2025. The US EPA has since introduced some of the world’s strictest drinking water limits—4 ng/L for PFOA and PFOS—and several states have enacted bans on PFAS in consumer goods and firefighting foams.

Europe and the UK

The Stockholm Convention [4] lists PFOS, PFOA, and PFHxS as persistent organic pollutants. The EU and UK, through REACH and CLP regulations, are exploring a broad ban on PFAS, including polymers, though temporary exemptions remain for critical uses.

Australia began restricting PFAS imports in 2002 and will ban PFOS, PFOA, and PFHxS from July 2025 under the Industrial Chemicals Act and Environmental Management Register Act.

Since 2016, Canada has prohibited PFOS, PFOA, and long-chain PFCAs, with newer regulations in 2025 classifying PFAS as a toxic class under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act (CEPA).

Global PFAS Drinking Water Standards

Around the world, governments are tightening drinking water guidelines to protect public health:

World Health Organization (WHO): 100 ng/L total PFAS (draft) [7]

European Union: 100 ng/L for 20 PFAS and 500 ng/L total PFAS [8]

Australia: perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS) – 8 nanograms per litre, perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) – 200 nanograms per litre, perfluorohexane sulfonic acid (PFHxS) – 30 nanograms per litre, perfluorobutane sulfonic acid (PFBS) – 1000 nanograms per litre. [11]

These increasingly strict standards reflect growing concern about PFAS contamination and its link to chronic diseases.

PFAS Cleanup and Remediation Efforts

Cleaning up PFAS is one of the biggest environmental challenges of the 21st century. Because PFAS resist degradation, they persist in soil, groundwater, and wastewater for decades.

Countries are adopting a risk-based, site-specific approach:

The US EPA provides compound-by-compound ecological guidance.

The Australian PFAS National Environmental Management Plan (NEMP), updated in 2025, offers standards for investigation and cleanup.

Canada now treats PFAS as a toxic class, enforcing emission controls and waste management.

Europe applies both PFAS-specific and general chemical risk frameworks, depending on the country.

These global efforts aim to reduce exposure, restore contaminated land, and protect wildlife and communities from PFAS accumulation.

The Road Ahead: Combating “Forever Chemicals”

PFAS represent one of the most complex environmental and public health challenges of our time. While regulations and awareness are improving, effective solutions will require collaboration between scientists, governments, and industries.

New technologies for PFAS destruction, remediation, and substitution are emerging, but widespread implementation remains a work in progress. As understanding deepens, so too does the global commitment to reduce—and ultimately eliminate—these persistent pollutants.

Updated: 5 December 2025

Section bibliography

Environmental Approach

Global Research

Section 1

PFAS

The Global Chemical Challenge Threatening Health and the Environment

Updated: 5th Dec 2025

Section 2

Global PFAS Regulations

How Countries Are Responding to the Forever Chemicals Crisis

Updated: 5th Dec 2025

Section 3

How Businesses Can Identify and Manage PFAS Risk

From Exposure Pathways to Sampling Best Practices

Updated: 1st Dec 2025

Section 4

The Science of Detecting PFAS

How Sampling and Analysis Shape the Fight Against Forever Chemicals

Updated: 8th Dec 2025

Section 5

Breaking Down Forever Chemicals

The Latest PFAS Treatment and Remediation Technologies

Updated: 1st Dec 2025

Section 6

The Future of PFAS Management

From Corporate Responsibility to Global Elimination

Updated: 1st Dec 2025

Section 8

Leading Through Change

How Companies Can Future-Proof Against PFAS Risks

Updated: 1st Dec 2025

Section 9

The Next Phase of the PFAS Response

Turning Knowledge Into Action

Updated: 1st Dec 2025 Find Out More >

Take Action

Address

N4, London, United Kingdom

Contact

Copyright © 2026 2Encapsulate Limited. All rights reserved.